Paleoenvironment of the St. Genevieve Formation

About the Church and the Choice of Kentucky Limestone

December 11, 1922.

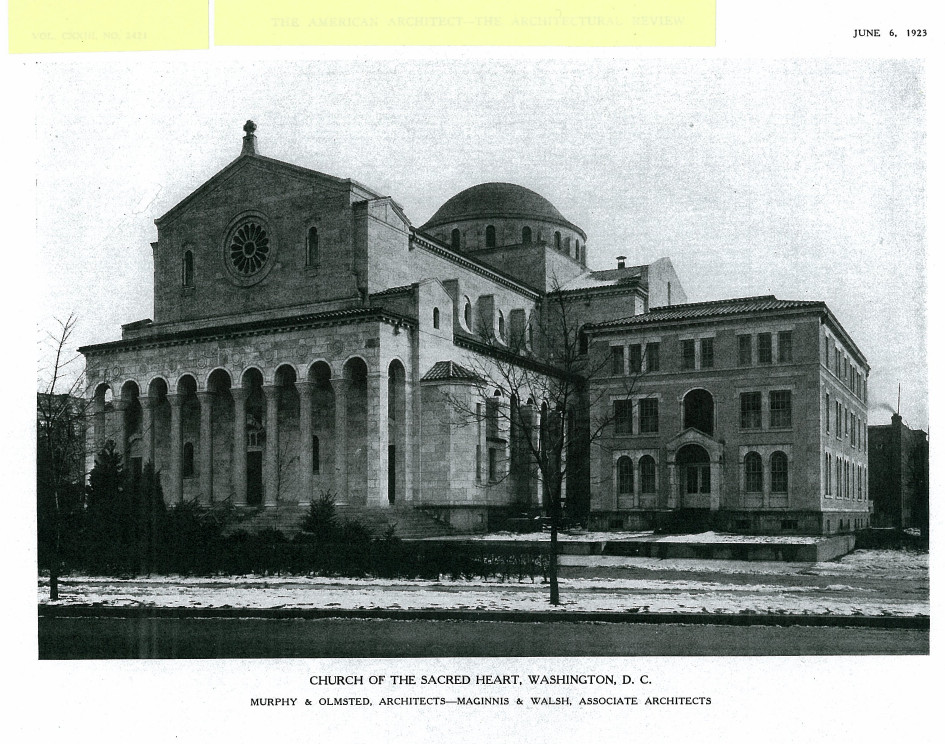

Through clear, cold hours morning hours, a large, well-dressed crowd gathered just behind the small park east of the intersection of 16th St. and Park Road, N.W. They were on hand for the consecration of a large new church and lacked the special passes needed to sit inside. Shortly before 10:00 a.m., incense rose as a procession walked from the rectory to the church. There, they were met by closed doors. An archbishop stepped forward and knocked. The doors opened to reveal a darkened church. The procession then joined well over 1,000 waiting inside. Amid lighted candles and chanted Latin, the Shrine of the Sacred Heart was consecrated. Outside, the crowd had to be content with viewing of a new church in the Northern Italian Romanesque style, with red tiled roof, shining marble columns, and walls clad in white stone. The Washington Post extensively covered the consecration of the Shrine – noting its size, costliness and the solemnity of its opening rituals. Below is a photograph of the church and rectory as they appeared at the time:

(photo from The American Architect/The Architectural Review, June 6, 1923, Vol. CXXIII, No. 2421, Plate 1, “Church of the Sacred Heart, Washington, D.C.”)

December 11, 2005

More than eighty years later on another cold, dry morning (very slightly warmer than in 1922), some changes are dramatic. A pedestrian walking north on 16th St. from Irving St. can still see the huge cruciform church and its rectory ahead, still clad in light grey stone.

A crowd was visible, but not dressed up in ceremonial best. Approaching the church on the east side of 16thSt., one works through a dense, block-long sidewalk bazaar, crowded with customers and sidewalk vendors selling homemade Central American food, Latino music CDs, and used goods of all sorts. Outside the church, other changes become apparent as well. At different times during the morning, voices inside the church are raised in French, Vietnamese, Spanish and English.

Little change is apparent in the building, however. Eight decades later, the exterior still matches the reports from the early years of “rich white” limestone “visible from a great distance.”

From a few feet away, the stone displays narrow bands of darker and lighter appearance:

Some of the stones display slanted bands that are cut off at the top by parallel bands – (reflecting “cross-bedding.,” see Gallery 6):

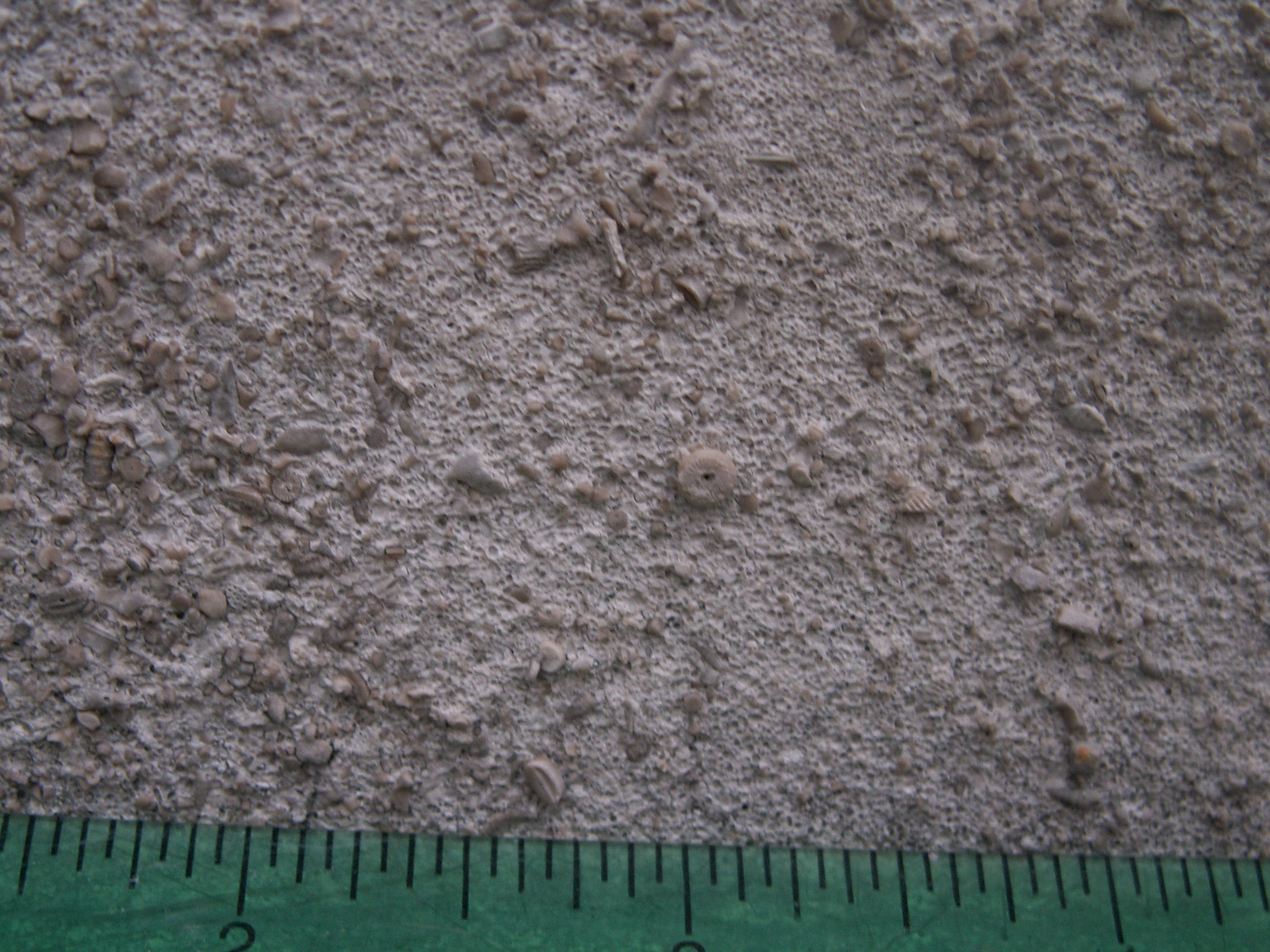

Closer still, the stone appears to be composed of fine grains and small fossil fragments:

It is a limestone from Kentucky. The stone resembles the Salem Limestone of Indiana discussed in Gallery 6, but is from a different geological formation, the St. Genevieve Formation. Both the Salem Limestone (350 million years old) and St. Genevieve Formation (326-330 million years old) were deposited during the Mississippian period, but they were slightly offset in both time and place — less than 200 miles and less than 30 million years separate them.

The fossils visible in the Kentucky limestone are tiny, fragmented and less varied than those in the Salem Limestone discussed at length in Gallery 6. Yet the Kentucky fossils illustrate an important point: not all grey, fossil-bearing exterior stones in D.C. should be assumed to be Salem Limestone. The Kentucky limestone is a representative of the many North American limestones types whose architectural use has been overshadowed by the omnipresent Salem Limestone.

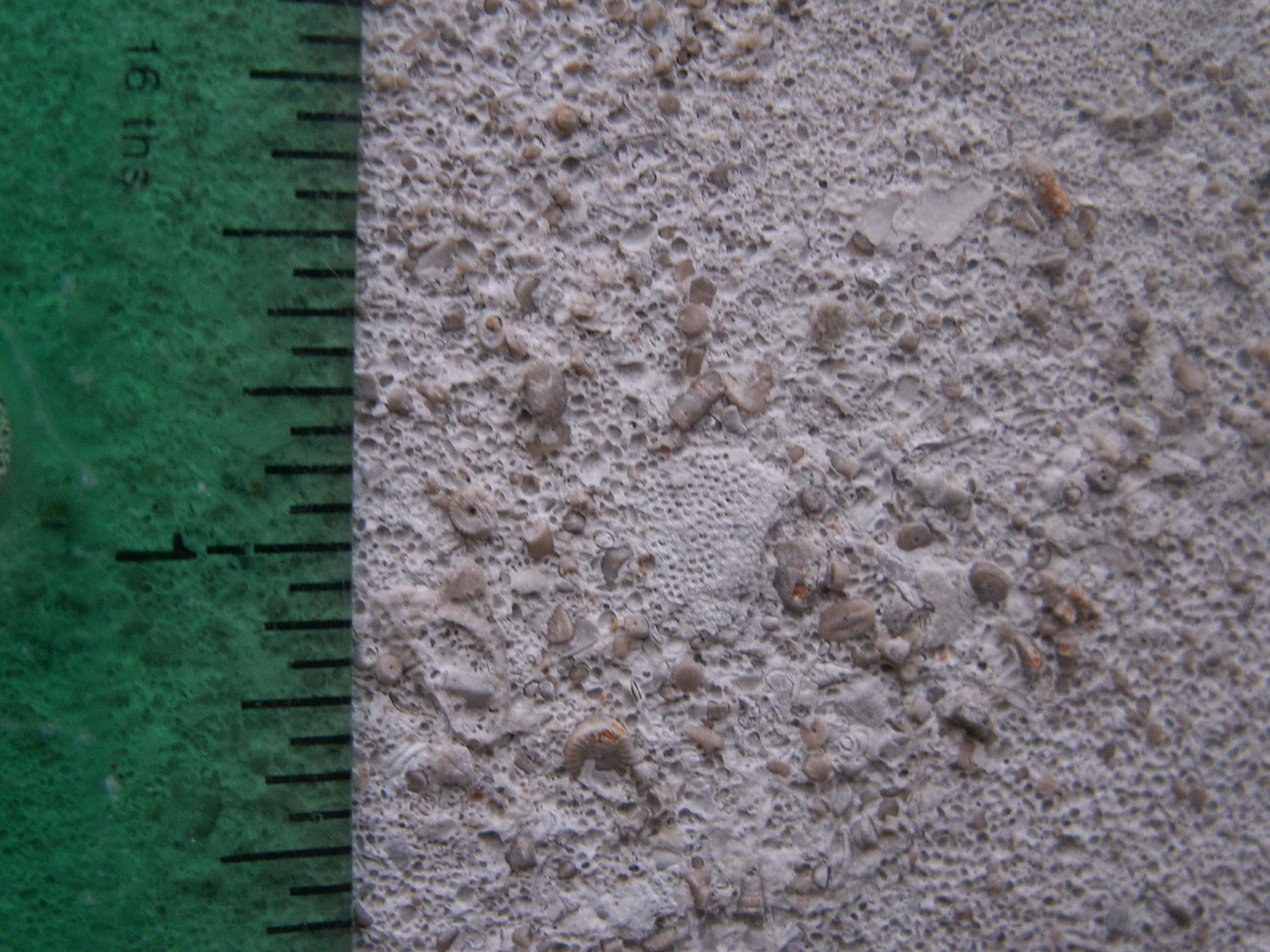

A close look at this stone shows a compressed mass, composed principally of small, rounded fossil fragments coated with calcium carbonate and relatively few readily identifiable fossils. One very clear fossil appears below, near the center and to the right of the ruler edge:

The life-saver-like disk is the columnal of a crinoid. Crinoids, filter-feeding animals also known as “sea lilies.” are discussed in detail in Gallery 9. Bryozoan fragments are also present, appearing below as tiny segments of tube-like, or short twig-like structures (bryozoans are discussed in detail in Gallery 6):

Shell fragments, crinoid columnals and bits of other invertebrate fossils appear below:

Paleoenvironment of the St. Genevieve Formation

The sediments that became the St. Genevieve Formation accumulated during the upper Visean age of the later Mississippian period, approximately 326-330 million years ago. They were deposited in a warm, shallow sea – one of a sequence of marine advances and retreats during this period. The St. Genevieve Formation principally formed in a subtidal environment – the cross-bedding suggests an active environment with currents. Conditions may not have been very different than those described in detail regarding the Salem Formation in Gallery 6.

About the Church and the Choice of Kentucky Limestone

At a time in D.C. when the overwhelmingly popular exterior limestone was Salem Limestone, why was Kentucky limestone used here?

The answer is not yet known, but the facts suggest two hypotheses.

First, contemporary accounts are unanimous on one point: the builders made every effort to create a striking and impressive church – from the design, to the interior, to the very materials, which many observed to be unusually costly. The architects were the prominent local firm of Murphy and Olmsted, assisted by Boston firm of Maginnis and Walsh, who were among the most important church architects in the United States. Great effort went into designing and executing the interior of the church, which featured hundreds of symbolic images – including animals, plants and allegorical references — worked in “exposed aggregate” concrete through the efforts of John Joseph Early. An American Architect article about the new church noted, “it may be truthfully said that the decorative theme briefly recapitulates the history of the church as well as its dogmas.” Structurally, the architects drew concepts from numerous Northern Italian churches of the Romanesque style, and employed detailed decorative and structural elements blending the practical and the symbolic. The church’s size and opulence partly reflects its immediate goal: to serve a burgeoning parish in a middle-class and well-to-do neighborhood; according to newspaper accounts, the parish had 3,000 members in 1921 and 5,000 member in 1924. A large and growing parish alone does not alone account for the intense effort to create a splendid and memorable structure, however. Location also played a part. The church faced the “Avenue of the Presidents,” and the American Architect noted that this locale, made it essential that the church building itself should be expressed in dignity and suggestive of repose, but skillfully differentiated from the many public and semi-public buildings that adorn, and will in the future be erected to compare with it. The richness of the material employed in execution of the building enjoys a certain distinction in being unique in the city of Washington. (emphasis added) Although this stretch of 16th St. did become known as “Church Hill” (see Gallery 12), the tides of development ultimately did not bring the grand neighboring structures that the builders may have expected. It is interesting to reflect that the church was made fit for a mighty company of edifices that never appeared.

One way to set the church apart would have been to depart from the Salem Limestone standard already apparent in the city by using the whiter stone of Kentucky.

The second hypothesis is based on the stone selection preferred by the architects. Sacred Heart Church was an impressive and unique structure even among other area Catholic churches – enough so that it was considered as a potential cathedral for the newly-created diocese of Washington after 1939. However, the architects’ use of Kentucky limestone was not at all unique to this church. Murphy and Olmsted, who were very active in designing buildings on the Catholic University of America and surrounding religious institutions, also used Kentucky limestone on the Mullen Library of the Catholic University (1925-28). Even before the construction of Sacred Heart, the associate architects, Maginnis and Walsh, designed the Notre Dame Chapel of Trinity College (1920-24), adjacent to Catholic University, with Kentucky limestone – they won the 1925 Gold Medal for ecclesiastical architecture for its design. In 1940, the new science hall at Trinity College was built of Kentucky limestone, and was designed to “harmonize” with other college buildings. So, Kentucky limestone was, during that period, popular with the ecclesiastical architectural firms operating in Washington – the choice may reflect nothing more.

Whatever the reason for the selection, the city is the richer for having yet another display of fossils.

Acknowledgments and References6

Special thanks are extended to Steve Greb of the Kentucky Geological Survey for his help in identifying the stone, and to Michael Gick, who loaned materials on the architectural background of the church.

Identification of the stone. The stone is identified as being from Kentucky in Sixteenth Street Architecture, Vol. 2, The Commission of Fine Arts (Kohler, S.A. and Carson, J.R., 1988. The stone in “Sacred Heart Church” in Washington D.C. is identified as being specifically the Bowling Green stone, in The Early White Stone Industry in Bowling Green and Warren County, by Christy Spurlock Smith, reproduced online by the Western Kentucky University http://www.wky.edu/Library/200Years.whtstone.htm The so-called Bowling Green Stone is from the Girkin Formation in the upper Mississippian.

However, geologists at the Kentucky Geological Survey examined photos of the fossils and concluded that based on identifiable fragments of crinoid plates from an index fossil, the stone did not appear to be from the Girkin Formation, but rather from the St. Genevieve Formation.

The architecture of the Shrine of the Sacred Heart Church building is discussed in Sixteenth Street Architecture, Vol. 2, cited above. Its architecture is also discussed in “Church of the Sacred Heart, Washington, D.C.” The American Architect/The Architectural Review, June 6, 1923, Vol. CXXIII, No. 2421, pp. 499-591 and Plate Nos. 1 through 9. Substantial additional background is found in the book, Substance, Form and Color through Concrete, published by the Atlas Portland Cement Company (1924), which chiefly focuses on the interior, but also has a contribution from the architect, F.B. Murphy (and supplies the 1920s woodcut at the end of the discussion below). The innovative “exposed aggregate” or “polychrome” concrete work of John Joseph Early is discussed in the Atlas Cement Co. book, as well as in other sources, including the website of the Franciscan Monastery in D.C., http://www.myfranciscan.org/index.cgi/229

Historical accounts of the church and its consecration, are drawn from a number of newspaper articles from the Washington Post: “New Sacred Heart Church Open Today,” Dec. 10, 1922, p. 29; “$1,000,000 Catholic Shrine Dedicated,” December 11, 1922, p. 2; “Mgr. Gavan Sympathetic, Dynamic, Able as Pastor,” September 21, 1924, p. HN14; “90 Children Confirmed by Archbishop Curley,” December 15, 1924, p. 9; “Public Opinion Divided on Church Architecture,” Aug. 30, 1936, p. AA5. Characterization of the weather for Washington, D.C. on the mornings of December 11, 1922 and December 11, 2005 is drawn from the daily historical data at the NOAA website, http://docs.lib.noaa.gov/rescue/dwm/data_rescue_daily_weather_maps.html.

Information about the geologic formation and paleoenvironment, The Mississippian and Pennsylvanian (Carboniferous) Systems in the United States – Kentucky, by Charles L. Rice, Edward G. Sable, Garland R. Dever, Jr. and Thomas M. Kehn, Geological Survey Professional Paper 1110-F, U.S. Gov’t. Printing Office, 1979. General information about Kentucky limestone, including the Bowling Green stone, is found at, Structural Materials, Advance Chapter From Contributions to Economic Geology, USGS Bulletin 430-F, 1909, “Oolitic Limestone at Bowling Green and Other Places in Kentucky” by James H. Gardner, reprinted online at “Stone Quarries and Beyond,” http://www.cagenweb.com/quarries/states/ky-oolitic_1909.html

Information about other uses of the Kentucky limestone in Washington is available at the Catholic University website, http://facilitiesoperations.cua.edu/floorplans/Mullen/ ,

and information about the use of Kentucky limestone at Trinity College in D.C. can be found at an online article from Trinity Magazine, http://www.trinitydc.edu/about/chapel/chapel.html , and “Trinity College to Build New Science Hall,” Washington Post, September 22, 1940, p. 75, and in the Christy Spurlock Smith work cited above, which identifies the Chapel at Trinity as using the stone.